|

LA CIVILTÀ CATTOLICA - O'Clery, Come fu fatta l'Italia (The making of Italy) |

THE MAKING OF ITALY1856—1870THE O'CLERYOF THE MIDDLE TEMPLE, BARRISTER-AT-LAW LONDON KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., Ltd. PATERNOSTER HOUSE, CHARING CROSS ROAD 1892 |

| (se vuoi, scarica il testo in formato ODT o PDF) |

PREFACE

It may be well to say a few words as to the authorities, on which is based the following narrative of the formation of the Italian Kingdom.

For the most part it is founded on information derived from Piedmontese and Italian sources, and on official documents, despatches and reports. These are referred to wherever they are quoted.

For the Franco-Austrian campaign of 1859 I have chiefly followed the official narrative of the war subsequently published by the French Staff under the title of “Campagne de l’Empereur Napoleon III. en Italie” supplementing and occasionally correcting it from other sources, and making use of the excellent critical analysis of the campaign to be found in the writings of General Hamley, since Napier, one of the best English writers on military matters.

For the Garibaldian campaigns of 1859—1862, I have made use almost exclusively of the narratives of Garibaldian and Italianist sympathizers—Commander Forbes, Colonel Chambers, M. de la Varenne, and others. In relating the inner history of the revolution in Sicily and Naples, I have made copious extracts from Admiral Persano’s diaiy and correspondence with Cavour, published at Florence in 1869, a work which deserves to be better known in England and in America.

The account of the “brigandage” rests mainly on statements made in the Parliaments of Turin and Westminster, and on Italian official documents. In the XVIIth Chapter the account of the events at Turin in September, 1864, is based on the report of the Commission appointed by the Italian Government. the history of the negotiations with Prussia, in 1865, is founded on the documents published by La Marmora.

The account of the war of 1866 is based on contemporary narratives and reports; for the details of Custozza and Lissa I have throughout relied upon Italianist sources of information. the same is true of the chapter on the revolt at Palermo, for which I have made use of the information contained in the singularly clear and able account of the rising, published in the Quarterly Review in January, 1867—an article based chiefly upon an unpublished Italian narrative, the work of an eye-witness who had no sympathy whatever with the insurgents. For the campaign of Mentana I have had at my disposal numerous narratives of both Papal and Garibaldian eye-witnesses, and this, moreover, is a period of which I can claim personal knowledge. In the account of the invasion of the Roman States in 1870 I have closely followed De Beauffort, whose work on the subject, with the mass of official documents it contains, is the best available authority upon it.

I have, throughout, endeavoured to give a clear narrative, just to all parties; and I trust that even those who do not agree with me in my view of these transactions, will find the work a useful record of the events in Italy from the Congress of Paris to the occupation of Rome by the Piedmontese—a period of which we have had until now no history in our language.

O’CLERY.

Temple, London,

March,1892.

CHAPTER I

CAVOUR AND NAPOLEON III

AMONG the Ghibelline families of Teutonic origin settled in the north of Italy, one of the oldest is that of the Benso. In the conflicts of the Middle Ages they were invariably found on the side of the German Kaisers. At a later period we see them holding high rank in the courts and armies of the Dukes of Savoy and Kings of Sardinia. In the last century the head of the family, Michele Benso, received the title of Marquis of Cavour, a small town in the province of Pinerolo; and Benso di Cavour, or more briefly Cavour, was henceforth the name of the family.

When Piedmont became a portion of the French Empire under the First Napoleon, the Cavours, faithful to the Ghibelline traditions of the family, allied themselves with the Imperial government in Italy. the Marquis Michele Giuseppe di Cavour held the office of Grand Chamberlain in the household of Prince Camillo Borghese, the husband of Pauline Bonaparte; and in 1810, when a second son was born to the house of Cavour, the Princess Pauline held the child in her arms at the font, and the Prince was his godfather, giving him his own name of Camillo. Born under the rule of the Bonapartes in the palmy days of the First Empire, the young Camillo was destined, as the Count di Cavour, to associate himself with the policy of the Second Empire, and bring the armies of another Bonaparte across the Alps.

Under the restored monarchy of Savoy, the young Count was placed at a military academy, and, later, received a commission in the Engineers, Curiously enough, his first work was to assist in planning and laying out a new fort to dose the road between Genoa and Nice, the very line of defence to which his policy afterwards transferred the Italian frontier. An over-free expression of Liberal ideas on his part led to his retirement from the army, a career for which he had little taste, and the loss of which he did not for a moment regret. To a friend, who wrote to condole with him, he replied: “I thank you for the interest you take in the matter; but, believe me, I shall make myself a career all the same. I have a great deal of ambition, an enormous ambition, indeed; and I trust I shall justify it when I am a Minister, for in my day-dreams I already see myself Minister of the Kingdom of Italy,”—bold words from a young man of little more than twenty years.

The next period of his life was one of travel and study.(1)It was not till 1847 that he made his first great step forward into public life, by founding, with Balbo, Santa Rosa, and Buoncompagni, the Risorgimento. the programme of the new journal was announced to be the advocacy of “the independence of Italy; union between the princes and peoples; progress in the path of reform; and a league between the Italian States —a programme in one sense satisfactory, in another of dubious import, for the words can be made to bear many meanings. At this time, however, Cavour might be called a Conservative, or at the very least what would be called in France a member of the Right Centre. It was not till some years after that he threw in his lot with the Liberals. In 1848 he was one of those who took the lead in obtaining the concession of a constitution by Charles Albert, and the following year saw him a member of the Piedmontese Parliament.

The accession of Victor Emmanuel, or rather the power placed by the constitution in the hands of the Liberals in the last year of his father’s reign, marked the beginning of a new era in the history of Piedmont. the Jesuits had already been expelled, in 1848, and an anti-Catholic law on education had been passed. the invasion of the rights of the Church in the Sardinian States was now the order of the day. the Piedmontese press, to a great extent in the hands of refugees from the other states, not content with attacking the political System of Rome, Naples and Austria, applauded the Government in its war against the spiritual jurisdiction of the Holy See. Three successive concordats had been signed by the kings of Sardinia in the pontificates of Benedict XIII., Benedict XIV., and Gregory XVI. the last of these, concluded in 1841, was still in force. After the events of 1848 the Cabinet of Turin had intimated to Pius IX. a desire that it should be modified in some respects. A plenipotentiary was named by the Pope to consider the matter; but the events which followed at Rome and Turin put an end for the time to the negotiations.

Next year Signor Siccardi was sent by Victor Emmanuel on a mission to the Papal court. The affair of the concordat was mentioned in his credentials, but, according to Cardinal Antonelli’s protest of February 9th, 1850, he never even approached the subject in the negotiations which followed, and which bore upon a different matter. He returned to Piedmont; and in the first week of February, 1850, the Pope and his Secretary of State learned, first by the newspapers and then by a despatch from the Pontifical chargé d’affaires at Turin, that Siccardi, as Minister of Justice, had introduced into the Piedmontese Chambers a bill to deprive the clergy of their privileges and immunities, to abolish certain holidays of the Church, and to deprive the priests and religious orders of the power of acquiring property in Piedmont In the name of the Pope, Cardinal Antonelli at once protested against these measures;(2) but, though stubbornly opposed by the Catholic party in the Senate, they passed both Houses, and received the royal assent on April 9th. They had already been condemned by the Holy Sce, and their execution was therefore opposed by the clergy and the episcopate. Two bishops and many priests were thrown into prison, and professors were driven from their chairs at the universities for maintaining the rights of the Church. Finally, when in August, by order of the Archbishop of Turin, the last sacraments were refused by a Servite father to Santa Rosa, the Minister of Commerce, because he kept to the last his adhesion to the Siccardi laws, the convent of the Servites was seized, the community dissolved, and the archbishop condemned to exile for life. It was in vain that Catholic members of the Senate protested that the Government, by its high-handed proceedings, was placing Piedmont in imminent danger of a schism. the Ministry (in which Cavour now held the portfolio left vacant by Santa Rosa’s death) persevered in its action against the Holy See. -

Acting upon these lines, the Minister of Public Worship took it upon himself to publish a circular regulating the teaching of theology in seminaries, and at the same time a civil marriage law was introduced into the Chamber of Deputies; it passed the Lower House, but the Senate rejected it by thirty-nine votes against thirty-six. the difficulty with Rome on the question of civil marriage led to the resignation of the Ministry, from which Cavour had already withdrawn. He was now sent for by the king, and requested to form a cabinet on the basis of an agreement with the Papal nuncio; but, being unable to obtain the consent of the latter to his own views on the subject of the marriage law, he declined to attempt the formation of a Ministry. the king endeavoured to find some one else to whom he could entrust the direction of affairs, but so strong were the Liberate in the chamber, that, meeting with no success, he sent for Cavour again. the count agreed to form a Ministry whose programme should be steadfast opposition to the Holy See. the king consented, and Cavour allied himself with Urbino Rattazzi, the leader of the Left Centre, and began his career as the Liberal and Revolutionary Prime Minister of Piedmont. “I would not have asked for anything better than to govern by means of and with the help of the Right Centre,” he wrote at this time to his friend, M. de la Rive, “and gradually to develop the institutions of our country; but it has been impossible for me to come to an understanding with that party on the religious question, therefore I must do without its support.” (3)With his new allies of the left he vigorously pursued the policy upon which he had accepted office. On March 16th, 1854, the goods of the episcopal seminary of Turin were sequestrated, and in August the “Canons of the Lateran” and of the Holy Cross were forcibly expelled from their houses in the capital. In November, Rattazzi, as Minister of the Interior, introduced in the Chamber of Deputies a bill for the suppression of all the convents and monasteries in the Piedmontese States, and for the sequestration of their property, financial reasons being openly alleged as the motive of this wholesale robbery. When the bill was sent up to the Senate in the following April, the bishops offered in their places in the House to come to the aid of the exchequer, and pay into it a sum of 900,000 francs, on condition of the withdrawal of the bill. But the Government, apart from all financial considerations, was determined to destroy the religious orders. the offer of the bishops was rejected, the bill was forced through the House, and became law on May 28th, 1855.

Cavour, with the aid of Rattazzi and the left, had thus fully developed that part of his policy which consisted in opposition to the Holy See. By the time that the bill for suppressing the monasteries had come before the Senate, he had begun to prepare the way for his main work—thè revolution which was to constitute that kingdom of Italy, of which he had been dreaming more than twenty years before. When the coup d’état placed France in the hands of the Bonapartists, Cavour was, as we have seen, a member of the Piedmontese Government. He had retired from the ministry before Napoleon III was proclaimed Emperor. Like every other thoughtful man in Europe, he saw clearly enough that the advent of the Second Empire meant not peace but war, and that the third Napoleon would retain his power only by endeavouring to emulate the military glories of the first In Italy the more far-seeing of the revolutionists from the first looked upon the new emperor as an ally. His first public act had been to join the insurgents of 1831. He had received his baptême de feu under the walls of Civita Castellana fighting against the troops of Gregory XVI. He had been regularly initiated into the secret societies, he was pledged by oath to labour for the cause of the Revolution in Italy, and in his person a Carbonaro was enthroned at the Tuileries. True, his troops had fought against the legions of Young Italy, torn down the Republican standard from the Capitol, and restored Pius IX; but, on the other hand, those who had closely followed the current of events, remembered that when Cavaignac first announced in the Assembly his intention of sending troops to Civita Vecchia, Louis Napoleon, then on the eve of his election to the presidency, had, through the medium of the press, entered a protest against the proposed Roman expedition (4): and that when Oudinot’s expedition was actually despatched, no one knew at first whether it came to support the Republic or to restore the Pope. Throughout, the policy of the President Louis Napoleon had been devious and double-faced. Had the triumvirs admitted Oudinot on the famous 30(th) of April, 1849, they might have found in him an ally, and but for Oudinot’s determination at all costs to avenge the defeat of that day, M. de Lesseps, as Louis Napoleon's agent, would have been able successfully to complete the negotiations which he had begun for the purpose of placing the Roman Republic under the protection of the French arms. Finally, in September, 1849, the President had written to Colonel Ney at Rome one of those despatches, which, though in the form of private letters, are meant to be made public and immediately find their way into the press. “My dear Ney,” he said, “the French Republic did not send an army to Rome to stifle Italian liberty there, but on the contrary to direct it by protecting it against its own excesses. ... I sum up in this sense the conditions of the restoration (5) of the temporal power of the Pope—a general amnesty, secularization of the administration, adoption of the Code Napoleon, and a Liberal Government.” He thus proposed imposing upon the Pope conditions, which in twelve months would have produced another revolution, and in any case would have made Rome a French city. Fortunately he did not persist in pressing his policy upon the Papal Court he had sufficient occupation at home in constituting and consolidating the Empire; but it foreshadowed his future action on the Roman Question.

While thus the more hot-headed members of the Revolutionary party denounced the coup d'état, and spoke and wrote bitterly of the man who had devised and executed it, their more clear-sighted leaders saw farther into the future, and knew that the crowned Carbonaro, Napoleon III, would at a later time be found on the side of the Italian Revolution. As early as 1852 Cavour took the first step towards cultivating friendly relations with him. Numbers of French refugees had crowded into Piedmont, and, through the press, vented their anger upon the new emperor. Cavour, on the plea that Piedmont should not be allowed to be involved by foreigners in a quarrel with France, procured the enactment of a new press law, which placed the newspapers under the strict control of the Minister of the Interior. Not only was this law useful for ulterior purposes, but it enabled him to prevent the press from speaking otherwise than respectfully of Napoleon III, while the Belgian press, uncontrolled by any similar law and inspired by exiles and refugees, was every day denouncing and insulting him. Napoleon cannot have failed to have remarked this contrast between the press of Belgium and of Piedmont. It was the beginning of the alliance between his policy and that of Cavour.

The Crimean war afforded the opportunity for the next step in advance. In January, 1855, a treaty of alliance was signed between England, France and Sardinia, by which the latter agreed to send 15,000 troops to the Crimea. This move of Cavour’s has been applauded by some of his admirers as an act of singular daring; (6) but there was very little courage required to enter as the ally of the two great Western Powers upon a war the result of which had been decided before a shot was fired, and doubly decided by the events military and political of the last six months of 1854. the Piedmontese troops, the pick of the large army maintained by Sardinia, were a welcome reinforcement, though the praises which have been lavished upon them, especially by Italianist writers, are rather exaggerated. the battle of the Tchernaya has been often spoken of as a splendid deed of arms of Della Marmora and the Sardinian contingent, a day which wiped out for ever the disgrace of Novara; but any one who takes the trouble to turn to a detailed account of the Tchernaya, (7) will learn that the brunt of the dose fighting throughout nearly the whole of the (1) battle fell upon the French, and especially upon Cler’s division, (2) that meanwhile the Sardinians assisted only by a well directed artillery fire, (3) that it was not till the battle was virtually won, that Della Marmora pushed forward into action a portion, and a portion only of his infantry and bersaglieri. the affair of the Tchernaya was substantially a French victory. the first Italian victory that followed the alliance between France and England was not in the Crimea. It was that which was won by Cavour at the Congress of Paris in 1856.

He had spoken in the Italian Chamber of the alliance, as giving to Italians an opportunity of showing that they could fight like brave men. “I am persuaded,” he had said, “that the laurels, which our soldiers will gather on the plains of the East, will profit more to the future of Italy than all that has been done by those, who have thought by declamations and by writings to effect her regeneration.” This was the view of his action which he wished to be taken by the press and the public; but in sending a Sardinian contingent to the Crimea, he was really seeking to gain for Piedmont access, not to the “field of glory,” but to the field of diplomatic action. He had been in Paris in 1855 with his sovereign, as the guest of Napoleon III, and he had held, it is said, conversations with the Emperor on the subject of Italy. He came again in 1856, as the joint representative with Villamarina of the kingdom of Sardinia. By right of the alliance, and notwithstanding the remonstrances of Austria, the representative of that little state sat side by side with those of the Great Powers, in that Congress which in its ultimate results has changed the face of Europe.

That to obtain a place in the Congress was Cavour’s object in sending the Piedmontese troops to the Crimea, and that the Crimean expedition was really the starting point of Cavour’s campaign for Italian Unity, was openly declared by Victor Emmanuel in 1860. On October 9th, he issued from Ancona his address to the people of the South, in which he said, “I have been able to maintain in that part of Italy which is united under my sceptre the idea of a national hegemony, out of which was to arise the harmonious concord of divided provinces united in one nation. Italy was put in possession of my view, when it saw me sending my troops to the Crimea by the side of the soldiers of the two great Western Powers. I desired to obtain for Italy the right of taking part in all transactions of European interest.”

The protocols of the Conference of Paris and the letters of Cavour (8) to his colleague, Rattazzi, who remained at the head of affairs at Turin, form a very complete record of the part taken by Piedmont in the Congress of Paris. On the 20th of February, the third or fourth day after his arrival at the French capital, he wrote to Rattazzi, “I have informed you in my special despatch of my conversation with the Emperor. I have little to add to what I said. I can only repeat that the Emperor would really like to do something for us. If we can assure ourselves of the support of Russia, we shall obtain something practical; but, if we do not, we must be content with an avalanche of assurances of amity, and good wishes. If I do not succeed, it will not be from any lack of zeal. I pay visits, I dine out, I write, I assist at meetings, in a word, I do all I can.” It was indeed a busy time with him. His one object was to have the affairs of Italy discussed at the Congress, and to commit Napoleon to an anti-Austrian policy. He saw the Emperor from time to time, but he was much more frequently with his cousin, Prince Napoleon, and he did not neglect to cultivate also the friendship of Lord Clarendon, in whom Cavour found an ally ready to the extent of imprudence to interpret his innuendoes and hints, until at length the two men spoke openly of war with Austria. In fact the alliance with the English Whigs was even older in date than the alliance of Piedmont with Napoleon III; and this because Clarendon represented, not so much England and his Sovereign, as the English Premier, Lord Palmerston, who had been for many years the best friend of the Italian Revolution.

At the sitting of the 8th of April, Cavour succeeded in his object of bringing before the Congress his own views upon the state of Italy. Strictly and legally the Congress had no more right to deal with anything but the affairs of the East, than it had to deal with the private affairs of any man in Paris. But on this occasion, as on many others, international law and right were quietly disregarded, in order to clear the way for subsequent schemes of aggression. Count Walewski, the Emperor’s \alter ego\ at the Congress, began to lead it beyond its legal competence by" referring to the Belgian press laws and the general tone of the Belgian press with regard to the Imperial Government. France, of course, did not wish to menace Belgium, but the tone of the press was a danger to the peace of Europe. Nothing was said of the press of Piedmont, for two sufficient reasons—first, Cavour’s press law of 1852 was a compliment which had not been forgotten, and secondly, the violence of the press was directed only against the Pope and Austria; and it mattered little that the Piedmontese press constituted a danger to the peace of Europe, now that France and Piedmont were actually designing an anti-Austrian alliance, the best preparation for which would be to irritate Austria against Piedmont, by means of the press or any other available method. the affairs of Belgium having been thus discussed in an assembly where she had not even the right of representation, M. Walewski called attention to what he styled “the abnormal condition” of the Papal States. the anarchy of 1848 had, he said, led France to occupy Rome, while Austrian troops held Ancona and the Legations. He admitted that there were solid grounds for this proceeding, but he went on to say that France was anxious to put an end to it at the earliest possible moment, (9) and he trusted that Count Buol would say the same for Austria. He might have added that the Pontifical Government would have been more pleased than either the court of Paris or that of Vienna to see the foreign troops withdrawn, and the States held by a Pontifical army alone. He then proceeded to speak of Naples, and, though there was no Neapolitan minister present, he urged that Ferdinand II. should grant an immediate and full amnesty to the exiles, who—as every one in the room must have known although he did not state it—were chiefly engaged in plotting against the government of the Two Sicilies in London, Paris and Turin.

Lord Clarendon spoke next. He dealt largely in generalities, but complained of misgovernment in the Legations and in Naples. Count Orloff refused to take any part in the discussion. He had come, he said, to assist in re-establishing peace, and the affairs of Italy had no part in his mission. Count Buol, the representative of Austria, was the next to speak. After alluding to a previous discussion, he turned to M. Walewski’s statement. It would be impossible, he said, to treat at that Congress of the affairs of independent states which were not even represented there. They could not occupy themselves with letting independent sovereigns know what they desired should be changed in the internal organization of their states. Nor could he follow Lord Clarendon in the observations he had made, and give any promise or declaration about the Austrian occupation of the Legations, although he joined M. Walewski in the wish that it could be prudently brought to an end. M. Walewski then rose to explain that no one had proposed that they should take any definite resolution, far less that they should interfere with independent states. He had only suggested that they should endeavour to complete the work of peace by occupying themselves in anticipation with complications which might arise from certain causes.(10) The causes to which he alluded were foreign occupations, a threat to Austria: a System of rigorous repression, a threat to Naples: the licence of the press, a threat to Belgium. This was hardly the way to complete the work of peace; it was rather sowing the seeds of war.

In reply to M. Walewski, Baron Hubner, the second Austrian plenipotentiary, reasserted the fact that he and his colleague had no power to deal with such matters; but he pointed out that the reduction of the Austrian garrisons in the Legations showed that the Imperial Government was anxious to put an end to the occupation. After Baron Manteufiel had remarked that the discussion of the affairs of Naples was only likely to produce a revolution in that country, Cavour spoke at some length. He did not, he said, dispute the right of any plenipotentiary to abstain from taking part in the debate, but he thought it important that the opinions which some of the Powers had expressed on the subject of the foreign occupation of the Papal States, should be set down in the protocol of the sitting. the occupation of the Legations, he said, had lasted seven years, and was assuming daily more and more of a permanent character. the condition of the country, he asserted, had not been improved. There was a state of siege at Bologna, and the presence of Austrian troops in the Legations and in Parma destroyed political equilibrium in Italy, and was a continual danger to Sardinia. As for Naples, he quite agreed with Walewski and Clarendon as to the necessity of an amnesty.

Baron Hubner made an able reply on the part of Austria. He called attention to the fact that Cavour had spoken only of the Austrian occupation, he had said not a word of the French garrison in Rome, although in their origin and in their object the French and Austrian occupations were exactly alike. That the state of siege existed at Bologna though it had ceased at An cona and Rome, only proved that the state of affairs at Bologna was abnormal and required an unusual remedy. But, he said, the Roman States were not the only Italian territories held by foreign troops. Sardinia had for eight years occupied Mentone and Roquebrune against the will of their sovereign, the Prince of Monaco. It is easy to laugh at this tu quoque of Baron Hubner to Cavour, but really it was highly honourable to Austria to adopt such an argument, for in so doing he asserted the first principle of international law—that, as municipal law is the same for all men whether rich or poor, so international law is the same for all nations, and a mighty empire and an insignificant principality can claim precisely the same rights and the same independence.

Cavour replied that he had not spoken of the French occupation, merely because he saw in it no danger to the independent States of Italy. It was, he said, quite different in this respect from the Austrian occupation. This was, of course, a direct menace on Cavour’s part to the Austrian dominion in the Lombardo-Venetian Kingdom; for the mere cessation of the Austrian occupation of Parma and the Romagna could hardly so materially alter the state of affairs as to remove this perii to the independent States of Italy, of whose rights Cavour showed himself such an active champion. As for Monaco, Cavour added that Sardinia was willing to evacuate Mentone, as soon as the prince could without any danger to his authority assume possession of it—precisely what Hubner had said of Bologna. His tu quoque was a complete success.

M. Walewski closed the discussion by remarking that the general result of it was that the Austrian plenipotentiaries agreed with those of France in desiring an evacuation of the Papal States by the foreign troops: and that the plenipotentiarics had agreed for the most part that it would be expedient for the Italian Governments, and especially that of the Two Sicilies, to adopt measures of clemency. Clarendon and Cavour left the room together. “Milord,” said the Piedmontese to the English minister, “Milord, you see there is nothing to be hoped for from diplomacy. It would be tinte to have recourse to other means, at least so far as regards the King of Naples.”

“Naples must be looked to, and that soon,” replied Clarendon, speaking quite in the spirit of his master, Palmerston.

“I shall come and talk it over with you,” said Cavour, as they parted. (11)

Next day he wrote to Rattazzi a private letter, supplementing an official despatch, which he had sent to Turin on the previous evening. He wrote of Clarendon as having spoken of the Pontifical Government as “the worst that ever existed.” “I believe,” he said, “his lordship, convinced that it was impossible to obtain any practical result, thought it well to use unparliamentary language.” From this it would seem that the discussion was considerably toned down in the protocol. He then tells Rattazzi of the few words he had exchanged with Clarendon after the sitting, and continues, " I think I can talk to him of blowing up the Bourbon. Italy cannot remain in her present position. Napoleon is convinced of it, and, if diplomacy be powerless, we should have recourse to means beyond the law. I am moderate in my opinions, and yet I am favourable to bold and extreme measures. In our times boldness is, I believe, the best policy. It has done good for Napoleon; it can also be of service to us.”

When Rattazzi read this letter, he evidently feared that Cavour had overrated the value of Clarendon’s declarations. He telegraphed to his colleague at Paris, “You are right; extreme measures are sometimes necessary. But do you not fear that England will abandon you, when it comes to a question of marching against Austria? As to Naples, whatever be the solution of the matter, if the Bourbon is driven out a step will be gained.”

Two days after, Cavour went to see Clarendon, to “talk the matter over” with him, as he had promised. (12) He told Clarendon that, in his opinion, the discussion of the 8th had proved two things—“(1) that Austria was determined to persist in her System of oppression and violence towards Italy; (2) that the efforts of diplomacy were powerless to modify her System.” Clarendon took all this for granted. He did not ask Cavour for the proofs, which he would have found it difficult to give. Neither of the two diplomatists descended to details and particulars; it was at once easier and more convenient to deal in generalities. In presence of this state of affairs, only two courses were open to Piedmont, either to be reconciled with Austria and the Pope, (13)( )or to prepare for war with Austria in an early future. “If,” he continued, “the first course should be found preferable, it would be my duty on returning to Turin to advise the king to recall to office the friends of Austria and of the Pope. If the contrary, the second idea, be the best, I and my friends will not fear to prepare for a terrible war, a war to the death, a war to the knife.” Here he stopped, to see what effect he had produced upon the English minister. Clarendon replied quietly, (<f) I think you are right; your position is becoming very difficult. I believe an explosion is inevitable, only the time to talk openly of it is not yet come.” Cavour replied, “I have given you proof of my moderation and prudence. I think in politics one must be extremely reserved in word, extremely decided in action. There are positions where less danger lies in a bold course than in an excess of prudence.

With La Marmora I believe we are in a condition to begin war; and, short as it may be, you will be forced to aid us.” Cavour had now drawn Clarendon beyond the bounds of prudence. “Oh! certainly,” he said; " if you are in a difficulty, you can count upon us, and you will see with what energy we shall come to your assistance.” “After that,” says Cavour, very naturally, in his letter, “I did not push the discussion further.” It had certainly gone quite far enough. Cavour was now confirmed in his project. Napoleon was with him, and so, he believed, was Palmerston. But there was this difference, which he failed to grasp—Napoleon meant France; Palmerston meant only the English Liberals. “I leave you to judge,” he wrote to Rattazzi, “of the importance of these words pronounced by a minister, who has the reputation of being a very reserved and prudent man... But as this is a question of life or death, we must act prudently. For this reason I intend to go to London, and consult Lord Palmerston and the other men who are at the head of the Government. If they share Clarendon’s views, we must prepare secretly, contract a loan of thirty million francs, and after La Marmora’s return send Austria an ultimatum such as she cannot accept, and begin hostilities. the Emperor cannot oppose this war. At the bottom of his heart he desires it. Before leaving here, I shall hold to him the same language I have used with Clarendon.” (14)

On the 13(th), (15) he and Clarendon dined with Prince Napoleon. They informed Cavour that the evening before they had spoken with the Emperor on the affairs of Italy, the Prince and the Englishman both, apparently, endeavouring to induce him to adopt a warlike determination, about which he still hesitated. the result of the conversation had been that Napoleon expressed a desire to talk matters over with Cavour in person. Accordingly the Count saw him, and spoke to him to the same effect as he had spoken to Clarendon, but in more measured terms. But the Emperor was more prudent than the English minister had been. He knew that to speak too plainly to Cavour would be to put himself in his power and unduly hasten matters, and besides he had not yet in any sense elaborated his Italian policy. He hoped, he said, to bring Austria to accept more conciliatory counsels. He had already remarked to Buol that he regretted to find himself in direct opposition to the Emperor of Austria; and Buol had told Walewski, in consequence of this remark, that Austria wished to please France in everything, and that they were really allies. Cavour looked incredulous. It is evident from his words to Rattazzi that his incredulity was twofold. He doubted Buol’s words to Walewski, and he doubted if the Emperor had ever spoken to Buol at all. It was necessary, he said to the Emperor, to open the question and take a decisive attitude. He had drawn up a memorandum, which he intended to hand to Walewski. the Emperor hesitated. Finally he advised Cavour to go to London, see Palmerston, and let him know the result on his return to Paris. Notwithstanding all Napoleon's prudent reserve, the two men understood each other. the alliance was already complete.

At the dose of that day’s sitting, an incident occurred, which Cavour took as a proof that Napoleon had really spoken to Buol. the Austrian Minister came to the Piedmontese Premier, and told him that his master wished to live in peace with Piedmont and had no desire to interfere with her institutions. Cavour replied, that during his stay in Paris Buol had given no proof of it, and that he believed the relations between the two countries were now worse than ever. At parting, Buol grasped his hand warmly, and said, “Let me hope that even politically we shall not always be enemies.” Three years later, in the same month of April, those two men exchanged an ultimatum and a declaration of war.

As early as the 27(th) of March, Cavour had addressed to Clarendon and Walewski a private note on the affairs of Italy; I shall refer to it later on. This note was the prelude to the memorandum presented to Clarendon and Walewski on April 16th, in which Cavour and Villamarina express their disappointment at the small results of the discussion of the 8th, charge Austria with exercising an intolerable tyranny in Italy, and in guarded language menace her with insurrection and war. Having taken this step, Cavour went on to London, and saw Palmerston. But a near relative of the Premier's had just died; he felt, or affected to feel, little disposed for the transaction of business, and Cavour could obtain from him no definite declaration, but only expressions of good will. He returned to Paris, disappointed but not discouraged. He saw the Emperor again; and, when he left the French capital for Turin, he felt that he had obtained sufficient assurances of the active support of France to enable him to begin at once the political campaign with Austria, the only object of which was, not to obtain any concessions from her, for these would have been fatal to his policy, but only to force her into war, a war in which the arms of France, and he believed those of England, would be upon his side.

CHAPTER II

THE ALLIANCE COMPLETED (1856—1859)

THE Congress of Paris was over. The first act of the drama had closed. Cavour was preparing for the second. There was a pause of three years in which no great events occurred. We may pass over them very briefly.

On his return to Turin, one of Cavour's first acts was to read to the Chamber the so-called verbal note which he had addressed to Walewski and Clarendon on the 27th of March. Briefly, it was a declaration of war against the Holy See. It was for Rome what the memorandum of April 1 6th had been for Austria. It arraigned the Pontifical Government on the double charge of incapacity and oppression, speaking of it as an ecclesiastical government, a theocracy in which laymen had no part. Reference was distinctly made to Napoleon's letter to Colonel Ney in 1849.(1) “Secularization and the Code Napoleon” this was the measure of reform it proposed for the Papal States. Then alluding to the Austrian occupation of Bologna, it urged that Romagna should be separated, at least administratively, from the Pontifical States. In the same sitting Cavour referred to the rumours of a rapprochement between Rome and Sardinia. He denied that there was any truth in them. After the reading of the verbal note, the denial was unnecessary. The newspapers freely but accurately interpreted it for their readers.

“In asking for the secularization of the Legations and their administrative separation from the Court of Rome,” said the Nord, (2) the Russian organ at Brussels, “M. Cavour has frankly expressed the hope that the practice of this system will lead to the independence of the Legations, and perhaps later on to their annexation to Piedmont. “This note,” wrote the Liberal Maga of Geneva, (3) “this note is the most solemn manifestation of the defiance given by the Sardinian plenipotentiaries to the Papal Government... It is a solemn cry of reprobation against the Pope, a programme of war against the Papacy both temporal and spiritual" And the Journal des Debats declared, “This is the beginning of the dismemberment of the Pontifical States.”

A week after the reading of the note in the Sardinian Parliament, M. de Rayneval sent M. Walewski an official note upon the then existing condition of the Pontifical States. De Rayneval had spent many years in Rome, and from his prominent official position the best sources of information were open to him. It was his interest to judge severely, and his memorandum was a private one, written solely for the information of his own Government.

It was not, like Cavour's “verbal note,” a manifesto meant for the ears of the European public. It was not written with knowledge drawn from secondary sources, but from personal acquaintance with his subject; and it furnished the most complete reply to all the charges made by Cavour against the temporal government of the Holy See. It was not until March, 1857, that it was published, and, strange to say, it was in the London Daily News that it first saw the light. How the Daily News obtained it, I do not profess to know; but in the leading Liberal journal appeared the best defence which has ever been written of the Roman administration. Its authenticity is undeniable. When it appeared, the Pays, then a semi- official paper, declared that the terms of the report had been seriously altered. the Daily News then pointed out that the writer in the Pays had used a version which had appeared in the Indépendance Belge, a version which had undergone a double translation, first from the original into English for the Daily News, and then back again into French for the Belgian paper: that it, therefore, was not surprising that it did not exactly correspond with the original text. But to set all doubts and cavillings at rest, the Daily News then and there published a copy of the despatch in the original French.

Here I can call attention only to some of M. de Rayneval’s chief statements. He begins by saying that the one point on which the Pontifical Government can be assailed is undoubtedly the partial occupation of its territory by foreign troops. “Every independent state is expected to suffice for itself, and to be able to maintain its internal security by its own forces. the Court of Rome is reproached with fading short of this reasonable expectation, the cause of its weakness is inquired into, and it is generally believed to be discontent awakened among its subjects by a defective administration.” He then proceeds to show that the discontent, so far as it exists, springs from a perfectly different source, namely, from the agitations of the Revolutionary party. This party wishes, he says, to make an Italy which shall play a great part in the world. “But how create a powerful Italy, so long as the peninsula is divided into two distinct parts by a state neutral from the necessity of its nature and isolated from all European conflicts? How play a great part, when the centre of Italy is in possession of a sovereign who does not wear a sword?”

Then he points out the tendency of the Italians to split up into factions. They have, he says, no cohesive power. It is a great error, he remarks, to take the Piedmontese as types of the Italians, for there is a large Swiss and French element in that nation. the population of the States is split up into parties. There are a certain number of Carbonari, and then there are the Mazzinians. “the universal republic, the unity of Italy, constitutional government, war against Austria, is their programme. They say they are a numerous body, and are ready to act, but they never keep their word. Directed by the committees of London and Geneva, their watchword for the present is quiet and inaction, until the return of their chiefs by means of an amnesty, and the departure of the foreign troops, give them an opportunity for acting with a chance of success.” Besides these there are the Moderate Liberate. “Refusing to go as far as the English constitution, there is a certain number of persons who profess attachment to the Pontifical Government, and at the same time overwhelm it with their attacks, pretending that they limit their desires to obtaining a better administration. They are not able to define exactly what they mean by this. In their eyes everything depends upon government, even to the proper maintenance of their own houses and the direction of their own affairs... Taxed as they are more lightly than the majority of European countries, they complain that they are weighed down with taxation... Finally, they profess to have a great fear of the Mazzinians, and at the same time are opening the door to them.” There is, he shows, an inertness in the mass of the people, which would make it difficult for any government, Papal or otherwise, to find a secure point d’appui in them.

In answer to the charge that the government is in the hands of priests and not of laymen, he remarks that people generally suppose that about three thousand ecclesiastics form the administration of the State, whereas there are really less than a hundred, and half of these are not priests, but only members of the Prelatura, which is practically a lay institution. Even some of the provinces had been placed entirely under lay control, only to the discontent of the people, who complained that the lay prefect thought only of his family, and asked for a prelate to govern them. In all the eighteen provinces, in 1856, there were just fifteen priests holding offices in the government. In Rome the proportion was higher, but the laymen were still in the majority. the numbers stood as follows :—

| Department | Ecclesiastics | Laymen |

| Ministry | I | 18 |

| Council of State | 3 | 5 |

| Court of Cassation | 9 | 8 |

| Tribunal of the Rota | 12 | 7 |

| Civil Tribunal | 3 | 116 |

| Tribunal of the Consulta | 14 | 37 |

| Criminal Tribunal | none | 58 |

| Episcopal Tribunal | 9 | 17 |

| Tribunal of Apostolic Chamber | 9 | 16 |

| Provincial Tribunals | none | 620 |

| Archives, Chamber of Notaries, &c. | none | 16 |

| Miscellaneous employés in Ministry of Justice | 1 | 6 |

| Ministry of Interior | 22* | 1411 |

| „ Finance | 3 | 2017 |

| ,, Commerce | 2 | 161 |

| „ Police | 2 | 404 |

| „ War | none | not stated |

* Including the fifteen chiefs of provinces mentioned above.

This table at once refutes the idea that the government was wholly ecclesiastical, that it was the government of a caste in which the people had no voice. In all there were less than a hundred ecclesiastics. “Is it possible,” asks M. de Rayneval, “to believe that the happiness and repose of the population are powerfully affected by the presence of such a small number of persons, who, I repeat, have for the most part nothing of the ecclesiastic but the dress?”

Pius IX., he says, has laid down and observed the principle, that with the exception of that of Cardinal Secretary of State, every office is open to the laity. “Different codes of procedure in civil and criminal cases, as well as a code relating to commerce, all founded on our own (the French), enriched by lessons derived from experience, had been promulgated. I have studied these carefully,” he adds; “they are above criticism. the Code des Hypoth'eques has been examined by French jurisconsults, and cited by them as a model document. the Roman law, modified in certain points by the canon law, was held as the basis of civil legislation.”

There was a Council of State, comprising, among its lay members, the Princes Orsini and Odescalchi, Professor Orioli, and the advocate Stoltz.

This council discussed and prepared all laws and decrees. There were also councils for the various ’ ministries, including a Council of Finance partly elected by the municipalities, the municipal councils themselves being elected by all the inhabitants of the commune, who paid a certain amount of taxes, or had taken high degrees in a university. Then, after giving further details as to the provinces, he adds:—“Abroad these essential changes introduced into the older order of things, these incessant efforts of the Pontifical Government to ameliorate the lot of the population, have passed unnoticed. People have had ears only for the declarations of the discontented, and the permanent calumnies of the bad portion of the Piedmontese and Belgian press. This is the source from which public opinion has derived its inspiration; and, in spite of well-established facts, it is believed in most places, but particularly in England, that the Pontifical Government has done nothing for its subjects, and has restricted itself to the perpetuation of the errors of another age.”

The Government had shown singular clemency in 1849. the most severe punishment inflicted had been exile; the number of these exiles in 1856 was estimated at about a hundred. the Government had, at serious loss to itself, bought up all the paper money of the Republican Government. In 1856 there was a good metallic currency, and also a certain amount of paper in the form of notes of the Roman bank, but these stood at par, and the bank was in a flourishing condition. Commercial treaties had been concluded with many foreign states, the custom-house tariff had been lowered, and the System of farming the indirect revenues had been abolished, the Government officials themselves collecting all taxes and duties. the debt had been reduced, and the deficit in the budget had grown yearly less, and was in 1856 almost extinguished. the administration was most economical, the civil list, expenses of cardinals, pontifical palaces and museums, costing altogether only 3,200,000 francs.

A Roman paid on an average 22 francs in taxes, a Frenchman 45. the army consisted of 12,000 native troops and 4000 Swiss. Numerous public works had been executed, drainage works carried out in the Marsh of Ostia and the Pontine Marshes, railways and telegraphs completed or undertaken, Rome lighted with gas, and steamers introduced upon the Tiber. Agriculture was encouraged. In a word, the States were prosperous. There was, of course, misery; but nowhere were there more ampie resources for relieving it. (4)

())“In truth,” says M. de Rayneval, “when certain persons say to the Pontifical Government, Form an administration which may have for its object the good of the people/ the government might reply, (4) Look at our acts, and condemn us if you dare.’ the government might ask not only which of its acts is a subject for legitimate blame, but in which of its duties it has failed. Are we then to be told that the Pontifical Government is a model, that it has no-weaknesses or imperfections? Certainly not;—but its weaknesses and imperfections are of the same kind as are met with in all governments, and even in all men, with a very few exceptions.”

Such was M. de Rayneval’s report. He was no optimist, he was not writing to order, or for the public; and his despatch is the best answer, a full and perfect answer, to the declamatory memorandums of the Count de Cavour.

Another answer was given in 1857, and a practical one. the Holy Father spent the four summer months, from the beginningof May to the first week in September, in a progress through his dominions. He was everywhere received with enthusiasm, and that enthusiasm reached its highest pitch in the streets of Bologna, where the state of siege had been raised by the special desire of the Pontifical Government.

In Piedmont Cavour was still pursuing his course of persecution against the Church. Pains and penalties were decreed by the Ministry of the Interior against any priest who withheld the last sacraments; the religious communities were gradually broken up, and their property sequestrated in execution of Rattazzi’s law; and, finally, the sees were kept vacant as the bishops died, until the episcopate of the kingdom of Sardinia was reduced by one fourth. At the same time he continued his preparations against Austria. Volunteers were incorporated into the Piedmontese army or formed into new corps, the fortifications of Alessandria were completed, and when they were ready to be armed a subscription for the cannon was opened in all parts of Italy by his agents. Austria withdrew her ambassador from Turin, but still with admirable patience avoided anything like an approach to war. She merely watched the Piedmontese armaments, and increased her own step for step with her enemy. But Cavour had more formidable weapons than those of the Piedmontese army. His embassies at the various courts of the sovereigns of Italy, were each the centre of a knot of conspirators. Indeed, the embassies of Piedmont, under Cavour’s influence, had superseded the vente of Carbonarism and the circles of Young Italy. Mazzini’s power was all but gone. He had been forced by the current of events to give way to the new campaign inaugurated by the Piedmontese Premier, though from first to last he was ready to denounce him as a monarchist who was depriving Italy of her true destiny, a Republican government. What we may call the last serious attempt of the Mazzinians was made in 1857. the Republicans, indeed, acted in earnest on other occasions, but it was as the willing or unwilling allies of Cavour. In 1857, they “fought for their own hand,” and failed. I notice the incident, less for its intrinsic importance, than because in the first place one of its leaders became at a later date Prime Minister of Italy, and in the second because Cavour’s condemnation of it is a condemnation from his own mouth of his own acts in 1860.

The Sapri expedition was planned and executed by Major Pisacane and Signor Nicotera, in the summer of 1857. It was contemporaneous with and formed a part of the same general plan of revolt as the Mazzinian outbreak at Genoa in the same year. Hence Cavour’s subsequent hostility to the project and its authors. Had they been able to jeter le Bourbon en Tair, as he himself desired, he would doubtless have been glad; but they tried at the same time to undermine and blow up the monarchy of Piedmont, and this was going too far. On the evening of June 25th, 1857, the Cagliari, a steamer belonging to the Compagnia Rubattino of Genoa (the same company whose vessels had later on the dubious honour of serving as Garibaldi’s transports), left the port with thirty-three passengers. Amongst these were Pisacane, Nicotera and twenty-three followers. As soon as the ship had got out to sea, they forcibly took possession of her, and directed her course to the island of Ponza in the kingdom of the Two Sicilies. There they freed and armed four hundred prisoners confined in the convict prison, and having recruited their forces with this very respectable contingent, they sailed again for Sapri, where they landed and dismissed the Cagliari. They were almost immediately attacked, not only by the Neapolitan troops, but also by the Urban Guard, that is to say by the armed inhabitants of the district, who were thoroughly loyal to King Ferdinand. the Republicans and the convicts were defeated and dispersed. Pisacane was killed, Nicotera severely wounded, and taken a prisoner to Salerno, where he remained till he was liberated by the revolution of 1860. On the 9th of July, 1857, Cavour wrote to Count Gropello, the Sardinian minister at Naples: —“This deplorable and criminal occurrence has excited the indignation of the Government of the king, and this indignation was shared by all sensible and honest men. You will therefore in my name express these sentiments to the ministers of his Sicilian Majesty.” Unfortunately two Neapolitan cruisers captured the Cagliari, as she steamed away from Sapri, an act which, natural as it was, the existing state of maritime law hardly justified. On board the steamer were two English engineers, and this gave Palmerston and Cavour a pretext for endeavouring to find ground for a quarrel with Naples. In this they would perhaps have succeeded, but Palmerston’s cabinet was driven from office by the Tories; and Lord Malmesbury, the new Secretary for Foreign Affairs, rightly considering that England had received all due satisfaction from the Neapolitan Government, quietly shelved the affair, regardless of the protests of D’Azeglio, who then represented Piedmont at the Court of St James’s.

But though in this sense he tried to make political capital out of the seizure of the Cagliari, Cavour throughout the negotiations never hesitated to condemn in the most ample terms Pisacane’s enterprise. On the 10th of January, 1858, he wrote again to Count Gropello :—”As soon as I received intelligence of the events at Ponza and Sapri, I hastened, through the medium of your Excellency, to give proof to the Neapolitan Government of the profound indignation felt by the King’s Government at the tidings of the criminal attack committed against the security of a friendly State.” And again he wrote :—”the violent incursion of Ponza and Sapri was the work of a few conspirators bent on a desperate enterprise, and it would be an abuse of the lawful meaning of words to confound these attempts—in which it is difficult to say whether the guilt or the madness be the greater—with a lawful state of public war. This would be the first time that a band of wicked and factious men were ever invested with the prerogatives of a belligerent power. the attempt of Ponza and Sapri was a crime of rebellion and robbery, and for its punishment the rules of ordinary penal law ought to be applied.” Cavour could hardly have used stronger terms, and in writing thus he put on record the condemnation of the precisely similar attempt of Garibaldi, which, thanks to his active participation, was a success, while Pisacane’s was a failure. (5)

The year 1858 opened with the Orsini plot, and the attempt of the Italian conspirators on the life of the French Emperor on January 14th. Cavour was startled. He feared, as he himself declared, that Orsini’s act would alienate the Emperor’s good will, and destroy all his plans. But he was mistaken. It did not for a moment alter Napoleon’s feelings, far less his plans. If anything, it only precipitated them. He, if no one else, understood the meaning of the act. It was an attempt which might be repeated, but which would not be repeated once he had publicly declared himself by his acts the ally of the revolutionary party in Italy. If he did not understand this on the night of January 14th, Orsini’s letter, written before his execution, must have pointed the moral to him. But, however this may have been, only another twelve month was allowed to pass before the decisive step was taken, and France found herself face to face with war against Austria. A definite plan of action was arranged in the summer of 1858. Cavour had obtained from the Parliament of Turin an authorization for a loan of 40,000,000 francs. the Parliament was prorogued on July 14th, and Cavour immediately set off for Plombières, a watering place in the Vosges, where Napoleon was then staying. At the interview it is believed that the Franco-Sardinian alliance was formally completed. Then, as if to diminish the importance of his interview with the Emperor, Cavour went on to Baden, where he saw the Crown Prince of Prussia (later the Emperor William I.). He then rejoined his colleagues at Turin. Europe in general dreamed only of peace. It was known that the relations between Austria and Piedmont were in a perilous state, but the French alliance was still a well-kept secret; and when the year closed, there were few who did not fully believe that no immediate causes of war were to be found in Europe. the first day of the new year put an end to this pleasing delusion.

CHAPTER III

CAVOUR AND NAPOLEON III

On the 1(st) of January, 1859, Napoleon III, surrounded by his court, received the diplomatic corps at the New Year’s levée at the Tuileries. No one expected that there would be anything more than the usual complimentary speeches, full of fine phrases, but really meaning little or nothing. What then was the surprise of the circle, when the Emperor, turning to Baron Hubner, the Austrian minister, said, in an emphatic tone and with an animated gesture, “I regret that our relations with your Government are not so good as they were, but I request you to tell the Emperor that my personal feelings towards him have not changed.”

Those who were present thought anxiously of the words of the First Napoleon to Lord Whitworth on the eve of the rupture of the Treaty of Amiens. the French funds fell five per cent.; and though an official note appeared in the Moniteur, asserting that there was nothing in the diplomatic relations with Austria to warrant the excitement and apprehension caused by the Emperor’s words, this attempt to mislead public opinion produced no effect in calming the fears of Europe.

The Sardinian Parliament was to open on the 10(th), and the King’s speech was looked forward to with intense interest; but, when it was delivered, it was found to be of the usual formal kind, and beyond an allusion to the clouded political horizon with which the year began, nothing was said either of the disputes with Austria or of the alliance with France. Two days after the Paris papers announced the probability of a marriage between the Princess Clotilde, a girl of fifteen, the only daughter of King Victor Emmanuel, and Prince Napoleon. the destined bride and bridegroom had not yet even seen each other. It was a purely political marriage; later we shall see its significance. On Sunday, the 23rd, the Prince arrived at Turin, accompanied by General Niel, who formally requested, in the name of the Emperor Napoleon, the hand of the Princess Clotilde for the Prince. Next Sunday the marriage took place, and Prince Napoleon went back to Paris with his bride. General Niel, who had the reputation of being the best military engineer in Europe after Todleben, remained in Italy, inspecting the fortresses of Piedmont.

Events travelled quickly, crowding upon each other. Austria was strengthening her garrison in Italy, asserting that her only object was to keep down the revolutionary party within her own frontiers. At Milan, Italianist proclamations were posted on the walls, and those who smoked government cigars were assaulted in the streets. the Sardinian army was concentrating in Piedmont, the troops being withdrawn from Savoy, the island of Sardinia and the minor provinces. In France preparations went on slowly and secretly. the arsenals were busy, whole regiments of soldiers were employed in cartridge-making, stores were being accumulated at the southern ports, rifled guns were being substituted for smooth-bores in the artillery, troops were concentrating at Lyons and Besanyon, the fleet was being assembled in the Mediterranean, the passes of the Alps were examined by engineer officers, and Niel was engaged with La Marmora on a plan for the defence of Piedmont until the French army could reach the field of action.

On the 4(th) of February, Signor Lanza, the Minister of Finance, rose in the Chamber of Deputies at Turin to ask for an authorization for a loan of fifty million lire. His speech was a bold one. He spoke of the well-known fact that in the previous month a fresh Austrian corps cTarmée had entered Italy. A strong army, he said, was massed about Cremona, Piacenza and Pavia, as if ready for an aggressive movement against Turin: detached corps held the villages: the export of horses into Piedmont had been forbidden, and the Imperial Government was contracting a loan of 150 millions of francs. In the presence of these facts the king’s Government asked for the loan, in order to continue preparations for defence. “We feel, gentlemen,” he concluded, “as much as any one the necessity of avoiding new burdens upon the country and an increased weight upon the finances of the State; and we are grieved to be compelled to propose them. But in the life of nations there arise, as you know, supreme moments, in which sacrifices are a sacred duty, an inevitable necessity. the Government, trusting to your known patriotism, does not doubt that you will be united and decided in conceding to it the means necessary for the defence of the country, and with it of the national honour, liberty, and independence.”

The debate on the loan followed, on the 9th. It is important from the light it throws upon the position of Piedmont and the results of the policy of Cavour. the \ debate was open ed by Count Solaro della Margarita, the leader of the Right. No one, he said, would beso base as not to rally round the king in time of danger, but when a question perhaps involving war was brought forward, it was necessary to examine carefully the truth of the statement that the country was in danger. Beyond any doubt the situation of the various provinces was anything but prosperous; commerce languished, agriculture suffered, manufacturers could not support a competition with the productions of other countries, the public funds were in discredit, and the indirect revenues were every day falling off.

“To speak candidly, gentlemen,” he continued, “if since 1849 we had quietly attended to the development of our institutions, if we had made it our chief care to promote science, art, and commerce, within our own limits: if we had not extraordinarily increased the taxes: if we had not held out allurements to the factions in all parts of Italy, and evoked hopes which for eight centuries have been nourished in vain: if we had thought more of improving our own lot, than of censuring and causing anxiety to other Governments—we should not have the name of agitators, nor should we see the plains of Lombardy inundated with Austrian bands; rumours of war would not arise on the Ticino.” the cabinet of Vienna, he asserted, was too prudent to involve its country in a general war; and for the cabinet of Turin also the most prudent course was to remain quiet; for Piedmont could not engagé in war withòut powerful allies, and then she would be at their mercy. To approve this loan would only be to sanction hostilities; and he, therefore, opposed the bill.

Count Della Rovere of the Centre replied in favour of the loan. He admitted that the finances were not flourishing; but he said he preferred liberty and debt to riches and slavery. He spoke of an Austrian invasion as imminent. He allowed that Cavour’s policy was a dangerous one, but, he added, all great things had their dangers. Piedmont was forced to look for foreign aid, because the other sovereigns of Italy preferred the Austrians a thousand times before the Piedmontese.

The next speaker was the Marquis de Beauregard, one of the representatives of Savoy. His speech was one of the most remarkable in the debate; for, when he spoke of his own country, though he evidently knew little of the French alliance, his words had an almost prophetic character. Savoy, he said, would yield to no part of the kingdom in its devotion to the public weal, yet he should oppose the loan. He refused to believe that the Austrian armaments were of an aggressive character. the French Emperor had publicly declared that the situation of Italy did not give any reason for war; yet Piedmont was arming, and it was proclaimed that the glorious moment had arrived to crown the policy to which the fortunes of the country had for eight years been sacrificed. “Count Cavour,” he said, “wishes for war, and he will do his utmost to provoke it. In the perilous situation in which his policy has placed us, war presents itself to his mind as the only possible chance of honourable liberation from the alarming debt which crushes us, and of fulfilling the engagements he has undertaken. If the existence of the monarchy of Savoy were not the stake he proposes in this terrible game, against the glory of associating his name with the deliverance of Italy, I could understand that the intrepidity of the minister might devote itself to an enterprise in which he probably believes that he has insured for himself all the chances of success; but those who have not the secrets of which he is master or his confidence in the future, recoil affrighted before the responsibility he has assumed. For my part,” he went on, “I will not give any encouragement to such a policy. I will not approve by a vote of confidence a policy which should always be opposed, a policy which has done so much injury to the internal situation of the country. I can inform you, gentlemen, that in Savoy the idea of a war is thoroughly unpopular. Borne down by heavy taxes, our people execrate the policy which imposes them on the country. But war would entail on Savoy an infinitely more deplorable fate than heavy taxation—it would lead to her separation from Piedmont. And, forsooth, we the inhabitants of Savoy are to shed our blood and wear out our resources for the purpose of placing ourselves under another crown. But do not imagine that the people of Savoy are less patriotic than others in the kingdom. No! when danger arrives we shall be among the first to strike a blow for our country. But we do not want to separate from the mother-country. I shall, therefore, vote against a bill which constitutes part of a policy necessarily leading to that result.”

These words created a deep impression in the House. the next speaker denounced the bill as amounting to a declaration of war; and Count Camburzano, who followed, asked what pledge had they of French assistance, had not Napoleon declared that his empire was peace? the honourable gentlemen on the left had by this time lost their patience. Camburzano sat down amid a storm of hisses, and Brofferio, the leader of the Radicate, springing to his feet, said he would vote for the bill and let Austria do her worst.

Count Cavour now ascended the tribune and all was still. To judge from his speech one would have supposed that the arsenals of Piedmont were idle, that its press and its public speakers had never alluded to Austria but in friendly terms, and that the Piedmontese propaganda in Lombardy and Venetia did not exist. He endeavoured to show that all the provocation was on the side of Austria, yet his speech was self-contradictory and a menace to Austria. His policy, he said, was not provocative. He did not arrogate to himself the right of initiating a war. His conduct had not become aggressive since the Congress of Paris, and he defied his opponents to prove their assertions. Yet he went on to say that the Government had a right to make itself in the face of Europe the interpreter of the wants, the sufferings and the hopes of Italy. the Government had, indeed, fortified Alessandria, but it was done because everything that had taken place in Paris convinced them of the impossibility of obtainingby pacific diplomatic means the complete solution of the difficulties of the Italian question. But why, it would be asked, were the Sardinian troops assembled on the frontier, why did he ask for the loan? Because Austria was massing her troops on the Ticino, and though she spoke only of peace, it might not be the first time that warlike intentions had been concealed by peaceful professions. (The very thing, let me note en passant* which Count Cavour was doing at that moment) He concluded by saying, he thought he had shown that his actions were not provocative, nor his policy inconsiderate.

He sat down amid loud cheers from the Centre and Left; but his eloquence had not carrried persuasion with it to all minds. Count Revel, who voted for the loan, admitted that the attitude of Austria was a suspicious one, but added, “this was the consequence, if not of the public acts of the Government, at least of the tone of the press, of its frequent menaces, of its frequent proposals that Austria might be attacked by us.”

The debate concluded in the midst of a scene of indescribable confusion. “Go to war as much as you please,” exclaimed the Savoyard, De Very, “that will not suppress the mountains which divide us from Italy; as a payment for the assistance you receive, we shall be annexed to —” the tumult made the rest of the speech inaudible. One member asked what would the Ministry consider a casus belli.

Cavour prudently declined to say what provocation they would consider as justifying an appeal to arms. Finally the bill was passed, 116 voting for and thirty-five against it. On the 18th it passed the Senate. But there was great difficulty in floating the loan. the Sardinian funds stood at a low figure, and several leading banking firms refused to have anything to do with it. (1)

While the bill for the loan was passing through the Parliament of Turin, events of great importance were taking place elsewhere. On the same day on which Lanza introduced the bill for the loan, Count Buol, the Austrian Premier, addressed a circular to the Imperial representatives at the courts of Europe, in which he urged the probability and the necessity of all Germany acting in concert in the event of Austria being attacked by France and Sardinia. As a kind of counter-manifesto, Cavour in the same way published a memorandum on the concentration of troops in Lombardy.

On the 7th of February, the French Chambers were opened. In his speech the Emperor deprecated the existing anxiety in the public mind, and repeated that the empire was peace. It had been his purpose on ascending the throne, he said, not to renew an era of conquests, but to inaugurate a System of peace, “which could not be disturbed except for the defence of great national interests, religion, philosophy and civilization a wide exception, considering that almost every casus belli recorded in history might be classed under one of these heads. He spoke of the troubled state ofhis relations with Austria, asserting that, under the circumstances, there was nothing to be wondered at in France drawing near to Piedmont. the state of Italy was, indeed, abnormal; but there was no reason for believing in war. Such was the effect of the more important passages of the Imperial discourse, which might be taken as an illustration of Talleyrand’s saying that speech was given to man to conceal his thoughts.

Far more light was thrown upon the Emperor’s designs by a pamphlet which was just then selling by the thousand in Paris. It had appeared a few days before, and already a large edition was exhausted. the title was,”L’Empereur Napoléon III et l’Ttalie.” It was known that portions of it were written by the Emperor himself, while the rest was composed under his inspiration. It was, in a word, the avowed expression of his policy.

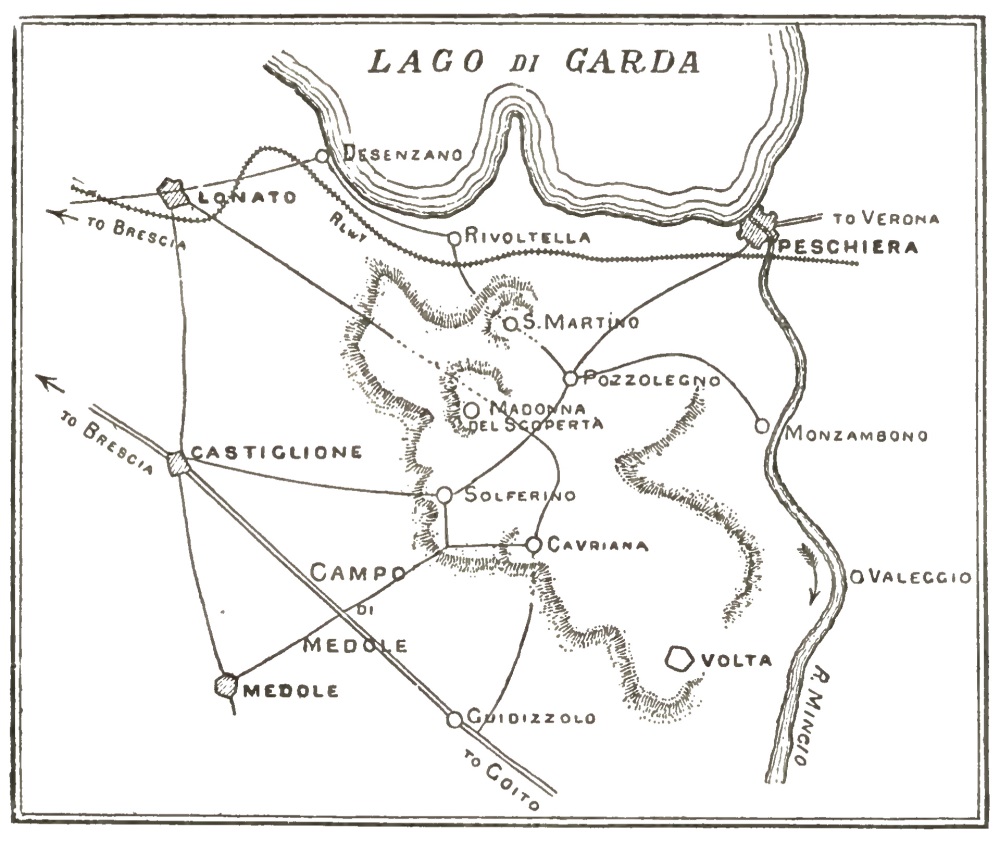

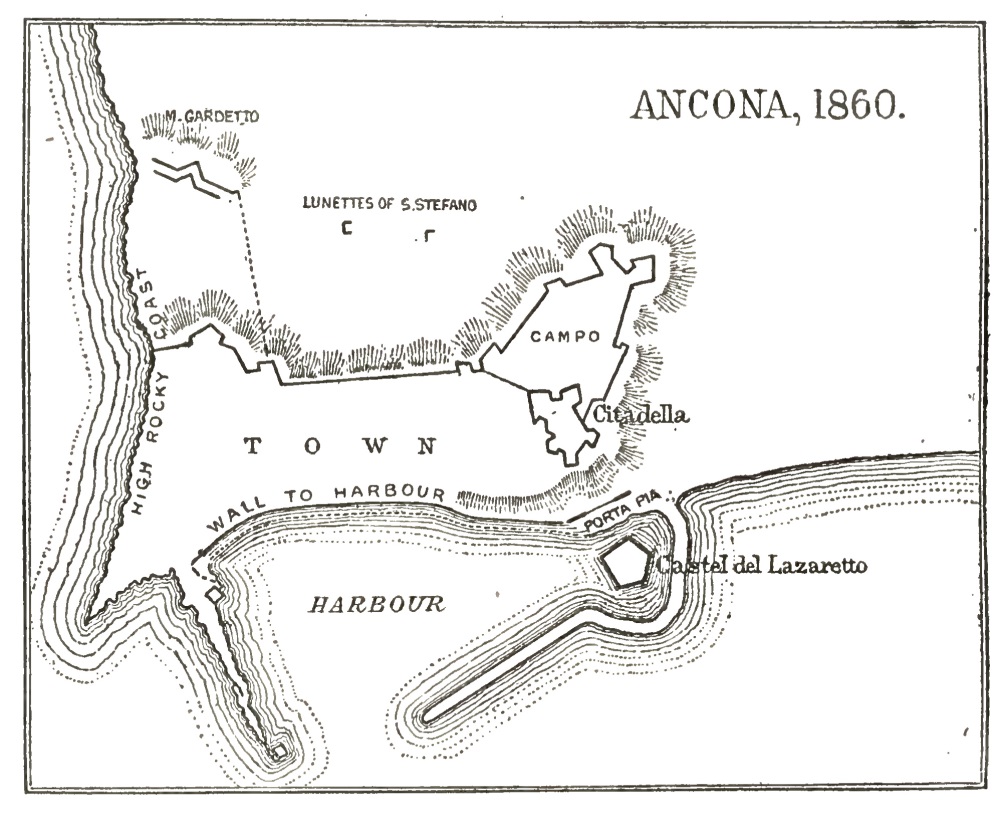

The pamphlet is an open attack on Austria. the Emperor seeks to prove that the position of Austria in Italy is untenable, her expulsion a necessity, the idea of her effecting useful reforms, if permitted to live in peace, an absurdity. An Italian confederation, he urges, is the only possible solution of the Italian question; but to this “there exists,” says the Imperial pamphleteer, “an obstacle beyond Italian and beyond European interest. It is Austria’s position in Lombardy. Opposition is the basis of Austrian policy. As Austria opposes reforms, so will she oppose everything else. What is to be done? Are we to bow to the veto of Austria? Are we to discard it? Are we to appeal to force or to public opinion to oppose this resistance?” There is, of course, a ready answer to the question. the idea of appealing to force is disclaimed. Heaven is asked to forbid it. the Italian question must be solved only by the influence of public opinion throughout Europe. Yet the language of the pamphlet points to war. the strength of the Austrian military position in Italy is elaborately investigated, with a view to proving that “Italian nationality will never be the result of a revolution, and can never succeed without foreign help.” But where is this help to come from? It is not openly stated that it is to be from France, but in more than one passage it is broadly hinted. It is “one of the traditions of French policy,” says the writer, “that the Alps, which are for her a bulwark, shall not become an armed fortress against her power.” Yet France does not wish for war, but “if France, which desires peace, were forced to make war, Europe would no doubt be moved, but she need not be alarmed; her independence would not be at stake. This war, which fortunately is not probable, would have no other object from the day when it became necessary, than to anticipate revolution by affording just satisfaction to the demands of nations, and by protecting and guaranteeing the acknowledged principles and authentic rights of their nationality.”